Your CI pipeline trusts 400 packages. Last week, one of them laid off 75% of its engineering team. Two years ago, another nearly shipped a backdoor to every major Linux distribution. Attackers are now registering package names that only exist because an AI hallucinated them.

Three incidents. Three attack vectors. One common thread: AI is reshaping software supply chain risk faster than most security programs can adapt.

You already scan for CVEs. You probably have an SBOM. But you’re likely not monitoring for maintainer burnout, AI-driven revenue collapse, or packages that only exist because an LLM invented them. Here’s a framework to close those gaps.

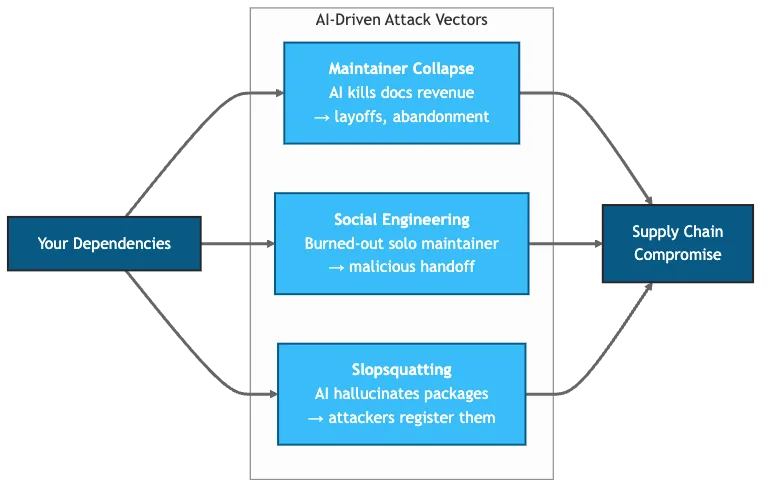

Figure 1: Three AI-driven attack vectors targeting your dependency chain.

Table of contents

Contents

What Are the Three Attack Vectors?

AI doesn’t just accelerate existing supply chain risks. It creates new ones.

Vector 1: Maintainer Collapse (AI-Accelerated)

On January 6, 2026, Adam Wathan attributed Tailwind’s layoffs directly to AI’s brutal impact on their business. Documentation traffic dropped 40%. Revenue collapsed 80%. Yet Tailwind CSS downloads keep climbing.

The mechanism is simple: developers ask Copilot for a Tailwind grid layout. The AI generates it. No documentation visit. No discovery of Tailwind UI. No conversion. The developer gets value. The maintainer gets nothing.

This isn’t a failing product. It’s a failing business model. And it’s not unique to Tailwind. Any project monetizing through documentation traffic faces the same exposure.

Meanwhile, curl maintainer Daniel Stenberg scrapped the project’s bug bounty program on January 21, 2026, citing “intact mental health.” Twenty AI-generated vulnerability reports flooded HackerOne in January alone. None identified actual vulnerabilities. Researchers paste code into LLMs, submit the hallucinated analysis, then loop follow-up questions through the same models. The result: maintainers spend hours triaging garbage instead of shipping code.

Different mechanism. Same outcome. AI extracts value from open source while accelerating the burnout that makes projects vulnerable.

Vector 2: Social Engineering of Solo Maintainers

In March 2024, Microsoft engineer Andres Freund discovered a backdoor in XZ Utils days before it would have shipped to most Linux distributions. CVE-2024-3094 scored a perfect 10.0. The backdoor enabled remote code execution through SSH on affected systems.

The attack took two years. A contributor using the name “Jia Tan” gained the sole maintainer’s trust through legitimate contributions, then inserted malicious code. The maintainer was burned out, working alone, grateful for help.

This pattern repeats. The event-stream incident in 2018 followed the same playbook: abandoned maintainer transfers control, attacker inserts cryptocurrency-stealing code. XZ Utils proved the technique works at infrastructure scale.

Two years later, the technique has evolved. Attackers now use LLMs to maintain technically helpful, perfectly patient personas over months, bypassing the “vibe check” that once caught human bad actors.

Vector 3: Slopsquatting (AI-Native)

This attack vector didn’t exist before LLMs. Slopsquatting exploits models that confidently recommend nonexistent packages. One in five AI suggestions points to a package that was never published (Spracklen et al., 2025).

The attack flow:

- Researchers run popular LLMs and collect hallucinated package names

- Attackers register those names on npm, PyPI, or RubyGems with malicious payloads

- Developers install AI-suggested packages without validation

- Malicious code executes

Unlike typosquatting, attackers don’t need to guess which names developers might mistype. The AI tells them exactly which fake packages to create. Names like “aws-helper-sdk” and “fastapi-middleware” appear in AI-generated code but never existed until attackers registered them.

The defense is straightforward: verify that packages existed before your commit date. This simple check catches AI-hallucinated packages that attackers registered after your AI suggested them:

import requests

from datetime import datetime

def check_package_age(name: str, commit_date: str) -> bool:

resp = requests.get(f"https://registry.npmjs.org/{name}")

if resp.status_code == 404:

return False # Package doesn't exist

pkg = resp.json()

published = datetime.fromisoformat(pkg['time']['created'].replace('Z', '+00:00'))

return published < datetime.fromisoformat(commit_date)scripts/validate_deps.pyCode Snippet 1: Detect slopsquatting by checking package age. Conceptual implementation only.

Why Does This Matter at Enterprise Scale?

The numbers are stark.

Sonatype’s 2024 State of the Software Supply Chain report documented 512,847 malicious packages discovered between November 2023 and November 2024. That’s a 156% year-over-year increase. The Verizon 2025 DBIR found that 30% of breaches now involve third-party components, double the previous year.

Log4Shell proved how fast these risks materialize. According to Wiz and EY, 93% of enterprise cloud environments were affected. Four years later, 13% of Log4j downloads from Maven Central still contain the vulnerable version. That’s roughly 40 million vulnerable downloads per year.

The projects in your dependency tree face these same pressures. The question isn’t whether you have exposed dependencies. It’s which ones, and whether you’re monitoring the right signals.

How Does the Two-Tier Ecosystem Create Different Risks?

Not all dependencies face equal exposure. A two-tier structure is emerging.

Tier 1: Foundation-Backed Projects

CNCF, Apache, and Linux Foundation projects operate differently. Kubernetes maintainers are typically employed by member companies. Corporate membership dues fund development. Governance structures distribute responsibility.

These projects face sustainability challenges: burnout, security maintenance burdens, contributor fatigue. But they’re insulated from documentation-traffic collapse. Their funding doesn’t depend on website visits.

Tier 2: Indie and VC-Backed Projects

Tailwind, Bun (pre-acquisition), curl, and thousands of smaller projects depend on sponsorships, consulting revenue, or VC runway. Many have single maintainers. The bus factor is often one.

These projects built the modern web. They’re also most exposed to all three attack vectors.

Your stack almost certainly spans both tiers. Kubernetes (Tier 1) might orchestrate containers running applications built with Tailwind (Tier 2). The risk profiles differ, and your monitoring should reflect that.

How Should You Assess AI Exposure Risk?

Traditional dependency scanning catches CVEs. It doesn’t catch maintainer burnout, revenue collapse, or AI-hallucinated packages. You need additional signals.

The 5-Signal AI Exposure Audit

-

Funding model: Corporate-backed or sponsorship-dependent? Check GitHub Sponsors, Open Collective, or company backing. Sponsorship-dependent projects face higher AI exposure.

-

Maintainer count: Bus factor greater than three? XZ Utils had one active maintainer. Look at commit history and active contributors over the past 12 months.

-

Governance: Foundation membership or solo maintainer? CNCF and Apache projects have succession plans. Solo projects often don’t.

-

AI exposure score: Docs-driven monetization (high exposure) or infrastructure utility (lower exposure)? UI libraries and developer tools face higher risk than compression utilities or parsers.

-

Recent signals: Layoffs, acquisition talks, burnout posts? Monitor project blogs, maintainer social media, and GitHub discussions.

Decision Thresholds

When should you act? Use this framework:

| Risk Level | Signals | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Monitor | 1-2 signals, Tier 1 project | Quarterly review |

| Watch | 2-3 signals, any tier | Monthly review, identify alternatives |

| Mitigate | 3+ signals, Tier 2 project | Sponsor, fork, or migrate |

| Critical | Active incidents (layoffs, security events) | Immediate review, contingency plan |

Table 1: Decision thresholds for dependency risk response.

Enterprise Application

Consider a fintech platform with 400 npm dependencies. Traditional scanning surfaces CVEs. The AI exposure audit surfaces different risks:

| Dependency Type | Count | High AI Exposure | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| UI frameworks | 12 | 4 | Review monetization models |

| Build tools | 8 | 2 | Monitor maintainer health |

| Infrastructure | 45 | 1 | Lower priority |

| Utility libraries | 335 | 23 | Automate monitoring |

Table 2: AI exposure audit across dependency categories.

The 23 high-exposure utility libraries aren’t all equal. Prioritize by criticality: is this in the authentication path? The payment flow? The deployment pipeline?

What Should CTOs Do Now?

Extend Your Toolchain

Your existing tools catch CVEs. Add tools that catch maintainer health:

- OpenSSF Scorecard (scorecard.dev) scores projects on maintainer activity, security practices, and bus factor

- deps.dev provides dependency graphs with contributor data

- Socket.dev detects supply chain attacks including slopsquatting patterns

Scorecard and Socket integrate directly into AI-augmented CI/CD pipelines via GitHub Actions, flagging risky dependencies before merge.

For a quick CLI check:

# Check a project's health score (0-10)

scorecard --repo=tailwindlabs/tailwindcssCode Snippet 2: OpenSSF Scorecard CLI checks a repository’s security health score (0-10).

To enforce this in CI, integrate Scorecard into your GitHub Actions workflow. The workflow below fails the build if a dependency scores below 7 out of 10, preventing risky dependencies from entering production:

- name: Run OpenSSF Scorecard

uses: ossf/scorecard-action@v2

with:

results_file: scorecard.json

- name: Block on low score

run: |

jq -e '.score >= 7' scorecard.json || exit 1.github/workflows/scorecard.ymlCode Snippet 3: GitHub Actions workflow to enforce minimum dependency health score of 7/10 in CI.

Validate AI-Generated Dependencies

If your teams use AI coding assistants, add a validation step:

- Flag any new dependency added in AI-assisted commits

- Verify the package existed before your commit date (see Code Snippet 1 in Vector 3 section)

- Check download counts and maintainer history

- Consider allowlisting approved packages

For teams using AI agents extensively, consider subagent architectures where a dedicated validation agent checks every dependency against registries and health signals before acceptance.

Sponsor Strategically

Sponsorship isn’t charity. It’s risk mitigation. If a Tier 2 project in your critical path shows stress signals, $500/month buys you a relationship with the maintainer and early warning on sustainability issues.

The companies that sponsored Log4j before Log4Shell had maintainer relationships when the crisis hit. The ones that didn’t scrambled with everyone else.

What Comes Next?

The OSS ecosystem is adapting. Bun’s acquisition by Anthropic shows one path: AI companies absorbing critical infrastructure. Expect more.

Experimental protocols like AICP (AI Consumption Protocol) and x402 attempt to let AI tools pay for documentation access. They’re unproven but conceptually sound.

The two-tier ecosystem is crystallizing. Foundation-backed projects will remain stable. Indie projects will face consolidation pressure. Some will be acquired. Some will be abandoned. Some will find new models. Others are relicensing. HashiCorp moved Terraform to BSL in 2023. Redis followed months later. Sentry, MariaDB, Elastic. The pattern is clear. When sponsorships fail and AI eats documentation revenue, restrictive licenses become the survival strategy. For enterprises, this means dependencies you assumed were permissively licensed may not stay that way.

For CTOs, the action is clear: extend your supply chain monitoring beyond CVEs. Track maintainer health. Score AI exposure. And remember that AI accelerates implementation, but humans must retain judgment, especially when validating what AI suggests you install.

But start with one question: open your package.json or requirements.txt. How many of those maintainers have you actually supported this year? The answer tells you how much risk you’re carrying for free. And how much you’re betting that someone else will keep paying the maintenance cost.

References

- CrowdStrike, “CVE-2024-3094 and XZ Upstream Supply Chain Attack” (2024) — https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/blog/cve-2024-3094-xz-upstream-supply-chain-attack/

- Goodin, Dan, “Overrun with AI slop, cURL scraps bug bounties” (Ars Technica, 2026) — https://arstechnica.com/security/2026/01/overrun-with-ai-slop-curl-scraps-bug-bounties-to-ensure-intact-mental-health/

- Snyk, “Slopsquatting: New AI Hallucination Threats” (2025) — https://snyk.io/articles/slopsquatting-mitigation-strategies/

- Sonatype, “10th Annual State of the Software Supply Chain” (2024) — https://www.sonatype.com/state-of-the-software-supply-chain/introduction

- Spracklen, Joseph et al., “We Have a Package for You! A Comprehensive Analysis of Package Hallucinations by Code Generating LLMs” (arXiv, 2025) — https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.10279

- Sumner, Jarred, “Bun is joining Anthropic” (2025) — https://bun.sh/blog/bun-joins-anthropic

- Verizon, “2025 Data Breach Investigations Report” — https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/reports/dbir/

- Wathan, Adam, “GitHub comment on Tailwind layoffs” (2026) — https://github.com/tailwindlabs/tailwindcss.com/pull/2388#issuecomment-3717222957