Single-agent AI coding hits a ceiling. Context windows fill up. Role confusion creeps in. Output quality degrades. The solution: multiple specialized models with structured handoffs. One model plans, another builds, a third validates. Each starts fresh. Each excels at its role.

Basic code assistants show roughly 10% productivity gains. But companies pairing AI with end-to-end process transformation report 25-30% improvements (Bain, 2025). The difference isn’t the model. It’s the architecture, specifically how you engineer the context each agent receives.

Anthropic’s research on multi-agent systems confirms what we observe: architecture matters more than model choice. Their finding that “token usage explains 80% of the variance” reflects the impact of isolation: focused context rather than accumulated conversation history.

This post documents a production workflow using Goose, an open-source AI assistant. The architecture separates planning, building, and validation into distinct phases, each with a different model optimized for the task.

Table of contents

Contents

- Why Do Single-Agent AI Coding Workflows Hit a Ceiling?

- How Does Subagent Architecture Solve Context Problems?

- How Does Model Selection Affect Cost and Quality?

- How Do Subagents Communicate?

- Where Should Human Judgment Stay in AI Workflows?

- What Results Does This Produce?

- When Does This Work (and When Doesn’t It)?

- Takeaways

- References

Why Do Single-Agent AI Coding Workflows Hit a Ceiling?

A single AI model handling an entire coding task accumulates context with every interaction. By implementation time, the model carries baggage from analysis, research, and planning phases. This stems from three core problems.

Context Bloat

Long conversations consume token budgets. The model forgets early instructions or weighs recent context too heavily. On-demand retrieval adds another failure mode: agents miss context 56% of the time because they don’t recognize when to fetch it (Gao, 2026).

Role Confusion

A model asked to analyze, plan, implement, and validate lacks clear boundaries. It starts implementing during planning. It skips validation steps. Outputs blur together.

Accumulated Errors

Mistakes in early phases propagate. A misunderstanding in analysis leads to a flawed plan. A flawed plan leads to incorrect implementation. Fixing requires starting over.

How Does Subagent Architecture Solve Context Problems?

The fix: spawn specialized subagents for each phase. An orchestrator handles high-level coordination and human interaction. Subagents handle execution with fresh context.

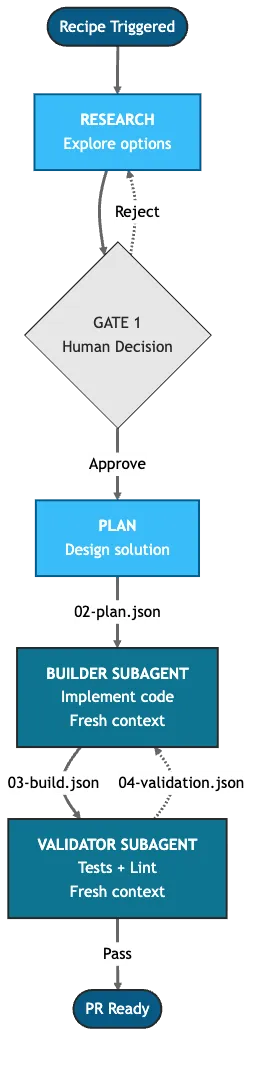

Figure 1: Core subagent workflow. Orchestrator handles RESEARCH (with human gate) and PLAN. Builder and Validator run as separate subagents with fresh context. SETUP and COMMIT/PR phases omitted for clarity.

The orchestrator (Claude Opus 4.5) handles RESEARCH and PLAN phases. RESEARCH requires human judgment at a single gate to decide the approach. After plan completion, it spawns a BUILD subagent (Claude Haiku 4.5) that receives only the plan, not accumulated history. The builder writes code, runs tests, then hands off to a CHECK subagent (Claude Sonnet 4.5) for validation.

Each subagent starts with clean context. The builder knows what to build, not how we decided to build it. The validator knows what was built, not what alternatives we considered. This is context engineering in practice: designing what each agent sees rather than letting context accumulate. This isolation prevents context pollution and drives the performance gains research attributes to architecture over model selection (Anthropic Engineering, 2025).

How Does Model Selection Affect Cost and Quality?

Different phases need different capabilities. Planning requires reasoning. Building requires speed and instruction-following. Validation requires balanced judgment.

| Model | Role | Temperature | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opus | Orchestrator | 0.5 | High reasoning for research and planning |

| Haiku | Builder | 0.2 | Fast, cheap, precise instruction-following |

| Sonnet | Validator | 0.1 | Balanced judgment, conservative (catches issues) |

Table 1: Model selection by phase. Temperature decreases as tasks become more deterministic.

Cost Optimization

Building involves the most token-heavy work: reading files, writing code, running tests. Routing this volume to cheaper models cuts costs significantly.

| Model | Input | Output | Role in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opus | $5/MTok | $25/MTok | Planning (~20% of tokens) |

| Sonnet | $3/MTok | $15/MTok | Validation (~20% of tokens) |

| Haiku | $1/MTok | $5/MTok | Building (~60% of tokens) |

Table 2: Anthropic API pricing, December 2025. Building consumes the most tokens at the lowest cost.

Research on multi-agent LLM systems shows up to 94% cost reduction through model cascading (Gandhi et al., 2025). This architecture targets 50-60% savings by routing building work to Haiku while preserving Opus for planning.

Beyond cost, fresh context enables tasks that fail with single agents. A 12-file refactor that exhausts a single model’s context window succeeds when each subagent starts clean.

Why Minimalist Instructions Matter

Smaller models like Haiku excel with focused, explicit prompts. Complex multi-step instructions cause drift. The recipe went through multiple iterations to find the right balance: enough context to execute correctly, minimal enough to avoid confusion. Each phase prompt fits in under 500 tokens. The builder receives a structured JSON plan, not prose. Constraints beat verbosity.

How Does Project Context Reach Subagents?

Recipes define the workflow, but subagents also need project context: build commands, conventions, file structure. That’s where AGENTS.md comes in, a portable markdown file that provides the baseline knowledge every subagent inherits. Goose, Claude Code, Cursor, Codex, and 40+ other tools read it natively. In Vercel’s evals (Gao, 2026), an AGENTS.md file achieved a 100% pass rate on build, lint, and test tasks where skills-based approaches maxed out at 79%.

Think of it as CSS for agents: global rules cascade into every project, project-specific rules override where needed. The orchestrator and every subagent it spawns inherit both layers without explicit prompting.

## Commits

- Conventional commits, GPG signed and DCO sign-off

- Feature branches only, PRs for everything

- Never merge without explicit user request

## Security

- Treat all repositories as public

- No secrets, API keys, credentials, or PII~/.config/goose/AGENTS.md## Stack

Rust 2024 + Tokio + Clap (derive) + Octocrab

## Project-Specific Patterns

- Apache-2.0 license with SPDX headers

- cargo-deny for dependency auditsaptu/AGENTS.mdCode Snippet 1: Global and project-level AGENTS.md files. The builder subagent from Table 3 inherits both layers: it knows to GPG-sign commits (global) and use cargo-deny (project) without either appearing in the handoff JSON.

How Do Subagents Communicate?

Subagents communicate through JSON files in $WORKTREE/.handoff/. Each session uses an isolated git worktree, so handoff files are scoped to that execution context. This creates an explicit contract between phases.

$WORKTREE/.handoff/

├── 02-plan.json # Orchestrator → Builder

├── 03-build.json # Builder → Validator

└── 04-validation.json # Validator → Builder (on failure)Code Snippet 2: Handoff directory structure showing the JSON files that pass context between phases.

The plan file contains everything the builder needs:

{

"overview": "Remove 4 dead render_with_context methods",

"files": [

{"path": "src/output/triage.rs", "action": "modify"},

{"path": "src/output/history.rs", "action": "modify"},

{"path": "src/output/bulk.rs", "action": "modify"},

{"path": "src/output/create.rs", "action": "modify"}

],

"steps": [

"Remove render_with_context impl blocks from each file",

"Remove #[allow(dead_code)] annotations",

"Remove unused imports",

"Run cargo fmt && cargo clippy && cargo test"

],

"risks": ["None - confirmed dead code"]

}.handoff/02-plan.jsonCode Snippet 3: Plan handoff file with structured task definition for the builder subagent.

The validator reads both 02-plan.json and 03-build.json to verify implementation matches requirements. It writes structured feedback to 04-validation.json:

{

"verdict": "FAIL",

"checks": [

{"name": "Remove #[allow(dead_code)] annotations", "status": "FAIL",

"notes": "Annotations still present in history.rs:145, bulk.rs:31, create.rs:63"}

],

"issues": ["Plan required removing annotations, but these are still present"],

"next_steps": "Fix issue: Remove the three annotations, then re-validate"

}.handoff/04-validation.jsonCode Snippet 4: Validation handoff file with actionable feedback for the builder to address.

The builder reads this feedback, fixes the specific issues, and triggers another CHECK cycle until validation passes.

Why files instead of memory? Three reasons:

- Auditable. Every decision is recorded. Debug failures by reading the handoff chain.

- Resumable. Interrupt and resume without losing state. Start a new session with the same handoff files and no work is lost.

- Debuggable. Failed validations include exact locations and actionable next steps.

Where Should Human Judgment Stay in AI Workflows?

Not every phase needs human approval. The workflow distinguishes between decisions (require judgment) and execution (follow the plan).

Phases with gates (human approval required):

- RESEARCH: “Which of these approaches should we take?”

- CHECK (conditional): On FAIL or PASS WITH NOTES, human decides whether to fix issues or proceed

Phases without gates (auto-proceed):

- SETUP: Initialize context and gather requirements

- PLAN: Design solution based on approved research direction

- BUILD: Execute the approved plan

- CHECK (on PASS): Validation passed, proceed to commit

- COMMIT/PR: Push validated changes

This separation preserves governance without creating bottlenecks. Humans make strategic decisions. AI executes. If validation fails, the system loops back to BUILD with specific feedback. No human intervention for mechanical fixes.

What Results Does This Produce?

This architecture powers development across multiple projects. Three examples from aptu:

| PR | Scope | Files Changed |

|---|---|---|

| #272 | Consolidate 4 clients → 1 generic | 9 files |

| #256 | Add Groq + Cerebras providers | 9 files |

| #244 | Extract shared AiProvider trait | 9 files |

Table 3: Representative PRs using subagent architecture. All passed CI, all merged without rework.

The validation phase caught issues the builder missed. In PR #272, the CHECK subagent identified a missing trait bound that would have failed compilation. The builder fixed it on the retry loop. No human intervention required.

Design Targets

Research on multi-agent frameworks for code generation shows they consistently outperform single-model systems (Raghavan & Mallick, 2025). The architecture is designed to achieve:

| Metric | Single Agent | Subagent Architecture |

|---|---|---|

| Context at build phase | ~50K tokens | ~5K tokens (fresh) |

| Rework loops | 2-3 typical | 0-1 expected |

| Human interventions | Throughout | Only at gates |

Table 4: Design targets based on context isolation and structured handoffs.

When Does This Work (and When Doesn’t It)?

Works well for:

- Multi-file refactors where context isolation prevents confusion

- Feature additions following established patterns

- Complex changes requiring distinct planning and execution

- Teams wanting audit trails (handoff files document decisions)

Less effective for:

- Simple one-file fixes (overhead exceeds benefit)

- Legacy systems without clear patterns (builder lacks context)

- Exploratory work where plans change during implementation

For teams integrating AI agents with legacy systems, see AI agents in legacy environments for integration patterns that work when your data lives in mainframes and AS400 systems.

Takeaways

- Separate reasoning from execution. Use capable models for planning, fast models for building.

- Fresh context beats accumulated context. Subagents start clean. They follow instructions without historical baggage.

- Structured handoffs create audit trails. JSON files document what was planned, built, and validated.

- Gates at decisions, not execution. Human judgment for strategy. Automated loops for implementation.

The full recipe is available as a GitHub Gist. It builds on patterns from AI-Assisted Development: From Implementation to Judgment.

References

- Anthropic Engineering, “How we built our multi-agent research system” (2025) — https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/multi-agent-research-system

- Bain & Company, “From Pilots to Payoff: Generative AI in Software Development” (2025) — https://www.bain.com/insights/from-pilots-to-payoff-generative-ai-in-software-development-technology-report-2025/

- Gao, Jude, “AGENTS.md outperforms skills in our agent evals” (2026) — https://vercel.com/blog/agents-md-outperforms-skills-in-our-agent-evals

- Gandhi et al., “BudgetMLAgent: A Cost-Effective LLM Multi-Agent System” (2025) — https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.07464

- Raghavan & Mallick, “MOSAIC: Multi-agent Orchestration for Task-Intelligent Scientific Coding” (2025) — https://arxiv.org/abs/2510.08804